Welcome to the Narrative Patient Centered Care online module. This module is presented in three parts:

I. Introduction to Narrative Patient Centered Care

II. Communication Skills for Narrative Patient Centered Care

III. Caring for the Whole Person and Family

In Part II, Communication Skills for Narrative Patient Centered Care, you will complete an interactive video case study in which you observe, analyze and reflect on the skills needed for a narrative approach to patient centered care.

UW photos, Northwest Scenes

"Never forget that you are also a story teller, that we live in stories the way fish swim in water, that we choose our stories, that we are made of stories."

Rebecca Solnit, author

He said it doesn't look good

he said it looks bad in fact real bad

he said I counted thirty-two of them on one lung before

I quit counting them

I said I'm glad I wouldn't want to know

about any more being there than that

he said are you a religious man do you kneel down

in forest groves and let yourself ask for help

when you come to a waterfall

mist blowing against your face and arms

do you stop and ask for understanding at those moments

I said not yet but I intend to start today

he said I'm real sorry he said

I wish I had some other kind of news to give you

I said Amen and he said something else

I didn't catch and not knowing what else to do

and not wanting him to have to repeat it

and me to have to fully digest it

I just looked at him

for a minute and he looked back it was then

I jumped up and shook hands with this man who'd just given me

something no one else on earth had ever given me

I may have even thanked him habit being so strong.

From All of Us: Collected Poems by Raymond Carver

Underlying the skills needed for Narrative Patient Centered Care is a significant difference in the approach you will take to gather information and make decisions with patients and families.

Shifting from the familiar biomedical approach to the narrative approach is not easy. Biomedical culture has powerful effects on our interactions with patients and families that are often outside of our awareness (Chen, 2007 and Gawande, 2014).

Consider the challenge and the rewards as presented in this brief comparison.

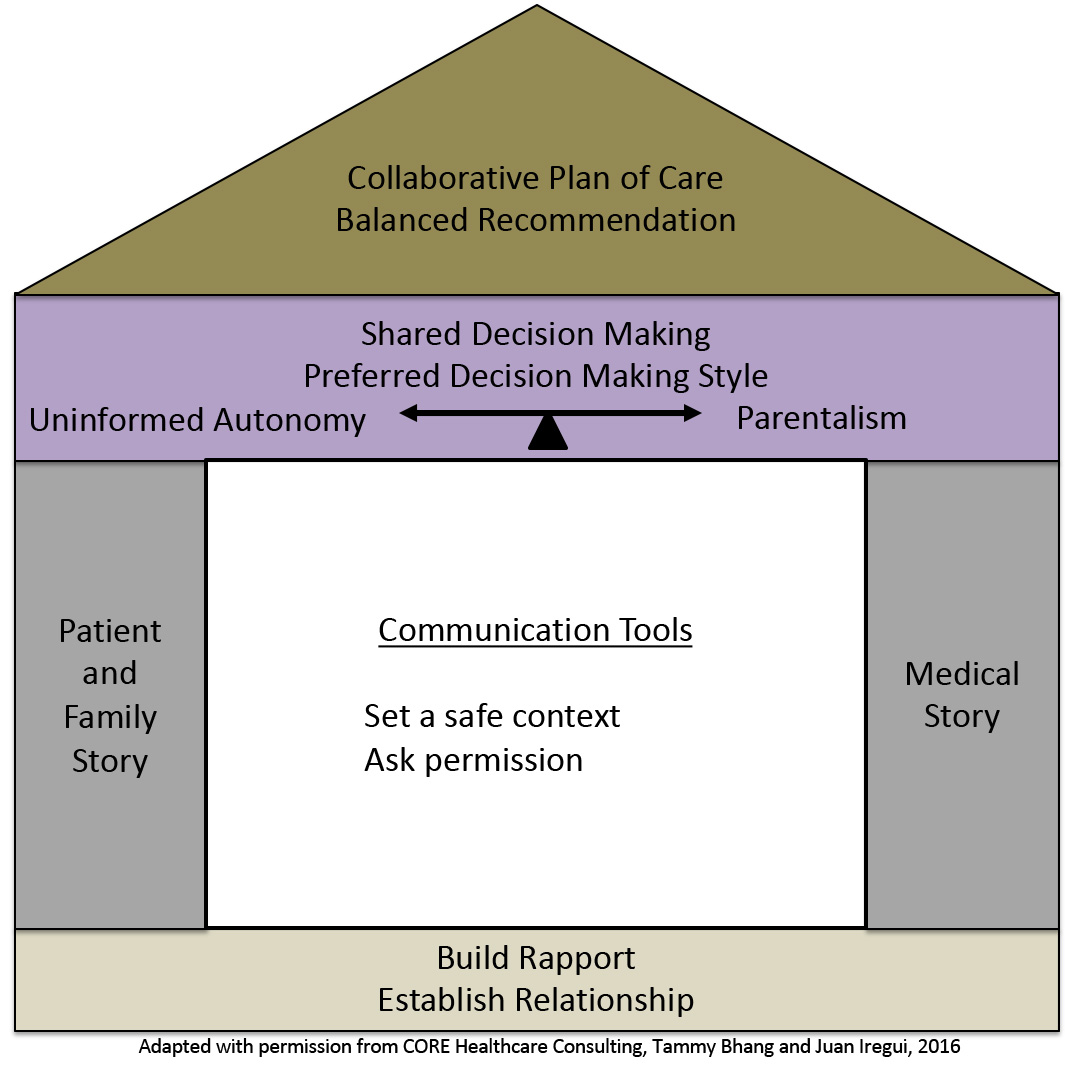

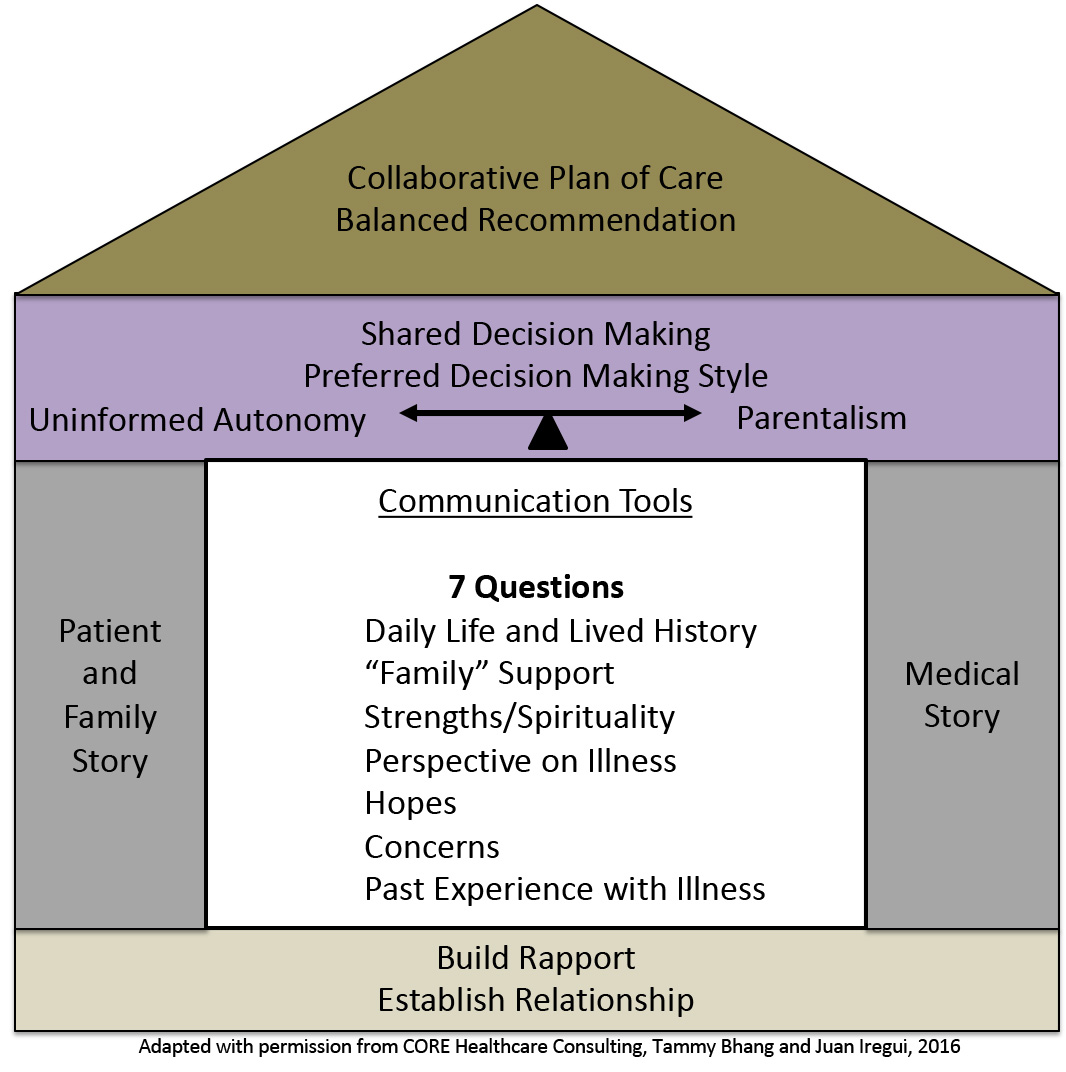

The communication skills needed for the narrative approach form the center of our House Model. We will add skills as we follow a patient, Wendy Jones, and her family in a video case study. The first two skills will be how to set a safe context and ask permission when eliciting a patient’s story.

Wendy Jones has been referred to your team for primary care because her previous primary care provider is no longer a provider in her Medicare insurance plan.

Wendy is a 67-year-old woman with a history of good health until five years ago.

A routine GYN exam revealed cervical cancer. A radical hysterectomy was done with clear margins and negative lymph node sampling. She recovered uneventfully but two years later she was found to have recurrence in the pelvis on a surveillance CT scan.

A second surgery was done for de-bulking and tissue confirmation followed by pelvic radiation and chemotherapy. She tolerated this treatment well and was again symptom free until six months ago when she developed a palpable recurrence on clinical exam.

The tumor failed to respond to several combinations of chemotherapy and the chemotherapy made her quite ill. Three weeks ago, her symptoms of increasing large bowel obstruction from her tumor necessitated a diverting colostomy.

She recovered well from surgery except for a small fistula. She continues to complain of significant pain despite frequent doses of Percocet (~6 tablets per day).

Most patients and families are accustomed to medical discussions focused on their disease with clinicians doing most of the talking.

For the patient and family, being asked to share their story in a healthcare setting is likely to be a new experience. It’s a discussion they are probably not expecting or prepared to have.

Watch the videos to observe Wendy’s first encounter with her new primary care provider. In the first video, the provider follows standard biomedical practices, in the second he takes a narrative patient centered approach. After watching each video you will be asked to identify the communication skills you observed.

Once you have set a safe context and asked permission to proceed, you can begin eliciting the patient and family story. Obtaining the patient and family "story" requires a considerable shift from the traditional medical interview. In order to provide patient and family centered care, we first have to understand their personhood beyond their illness and get a picture of day-to-day life. This is the first of what we call the “7 Questions.”

Click on this link to see all 7 Questions

Creating a picture of our patient’s lives involves approaching these conversations with a sense of curiosity. An exercise that can be helpful is to imagine you are meeting your patient for the first time outside of your normal roles, at a neighborhood gathering. In the boxes below, write out ten questions you might ask to get to know them, then click on “feedback” to see some examples:

After you have a sense of your patient’s personhood, you can start to shift the conversation to their experience with their current illness. To start this part of the conversation, the first step is to assess their perspective on the situation they are facing now. This is question four on the list of “7 Questions.”

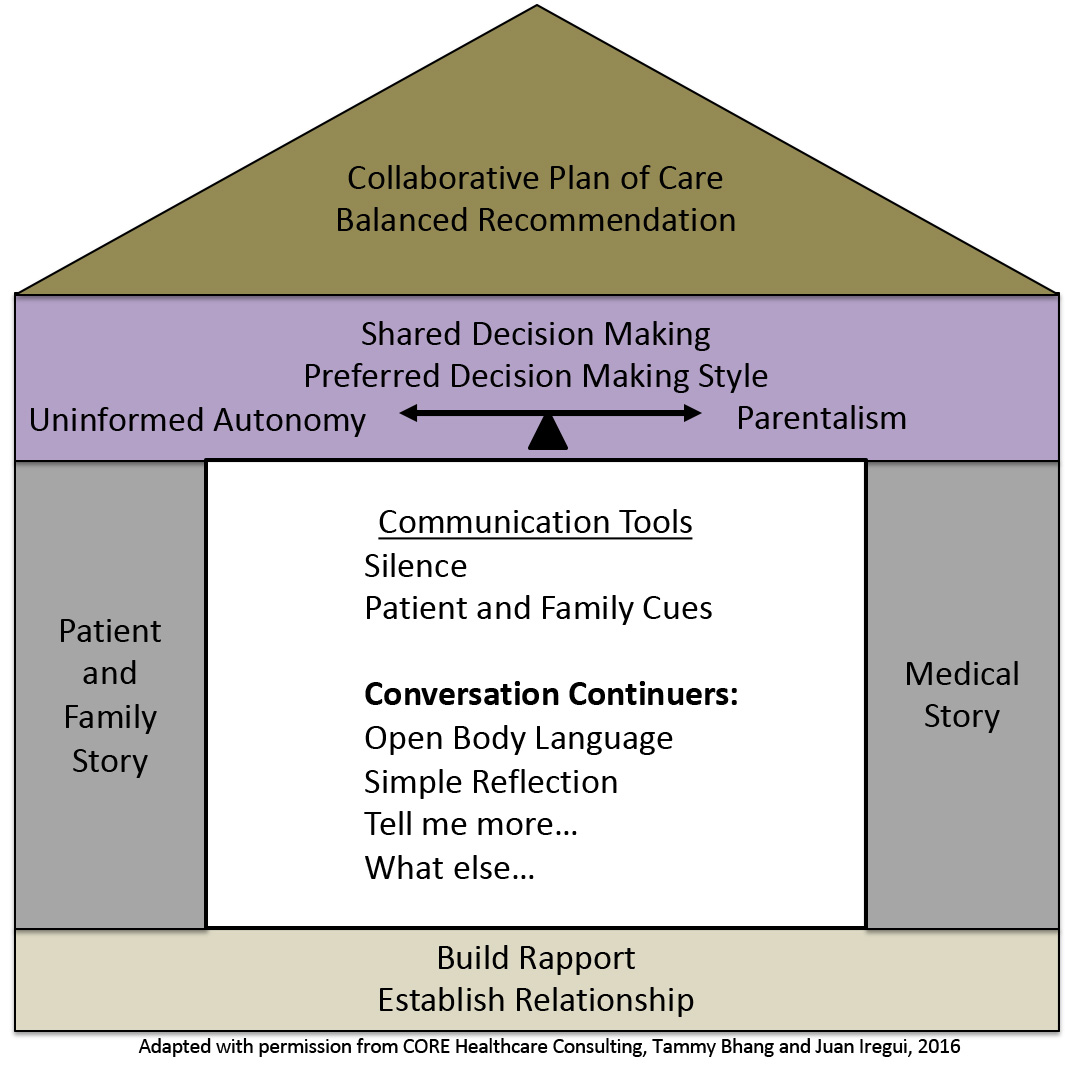

We will revisit the rest of the 7 Questions in Part 3 when you meet Wendy’s family. For now, we will add a few more tools to the communication toolbox to further deepen our understanding of the patient and family story. A narrative dialogue with patients is akin to a dance where both partners trade off leading. The clinician uses the 7 questions as a guide (e.g. dance steps) to facilitate the conversation and they use other communication skills to help engage the patient, or family, more deeply in the conversation. This creativity in the dance comes from adding the following tools: silence, identifying cues and using “conversation continuers” to explore the cues.

Patients often need much more than a few seconds to adequately self-reflect when answering questions such as “What are you hoping for?” or “What are you concerned about?”

Periods of silence lasting 7-15 seconds can be powerful invitations for a patient to share deeper values and meaning.

Silence is not the absence of communication but a rich opportunity that allows patients to access memories and experiences to provide deeper answers to our questions.

A. Doorenbos, pain module

Research shows that the average physician can tolerate silence in a conversation for an average of 7 seconds.

Intentional silence, versus silence of distraction or discomfort, can build emotional connection with patients.

Bartels et. al Patient Educ Couns 2016.

Patients and families living with serious illnesses will provide cues to clinicians that they have important personal and emotional concerns they wish to discuss

“Patient cues” are verbal and non-verbal indications that the patient or a family member has unspoken emotionally charged concerns.

"Continuers" are verbal and non-verbal responses that acknowledge the emotions being expressed and encourage the patient or family to share more about their concerns.

Patients’ cues are windows of opportunity for exploring the patient's story in more depth and sharing deeper emotional, existential and spiritual truths that underscore values and meanings.

"Terminators" are verbal and non-verbal responses that focus on biomedical facts and ignore the emotions patients and family are expressing.

Simple Reflection: When a clinician repeats what the patient said using similar words to let them know they heard the information. It often starts with “It sounds like…” or “What I’m hearing…”

Open Body language: Keeping open body language such as leaning forward, nodding, uncrossed arms and facial expresses that reflect the emotional tone show you are actively listening.

“Tell me more” and “What else”: These phrases invite patients to expand on a topic they reference briefly and usually uncovers key information about values or underlying concerns.

“Continuers” won’t work with everyone.

Not all patients are comfortable or willing to share their emotions.

If you use “continuers” and get little response, be respectful of the patient’s and family’s limits and stay within the boundaries they set in sharing their story.

A. Doorenbos, pain module

Observe the differences in the attempts to obtain Wendy’s story in the videos below. After watching each video you will be asked to identify the communication skills you observed.

After obtaining the patient’s and family’s story, summarize and confirm what you’ve heard.

Summarizing and confirming the narrative creates a path to common understanding.

A. Doorenbos, pain module

Observe the differences in the attempts to summarize and confirm Wendy’s story in the videos below. After watching each video, you will be asked to rate the clinician’s use of Narrative Patient Centered communication skills.

In the Part III, you will observe Wendy’s follow-up visit with her provider and learn about Whole Person dimensions of Narrative Patient Centered Care.

UW photos, Northwest Scenes