Dr. Stuart Farber was the founder of the Inpatient Palliative Care Service at the University of Washington Medical Center and the UW Palliative Care Training Center (PCTC), which oversees the Graduate Certificate in Palliative Care.

Stu was known for being a gifted story teller, teacher, healer and artist. He also was a dedicated husband, father and grandfather. Stu encouraged us all to become editors for our patient's stories. He said, "A good editor tells your story for you, a great editor helps you tell your story better."

Stu died shortly before the first PCTC course was launched and will be greatly missed. This 3-part module on Narrative Patient Centered Care was envisioned by Stu and is a collection of his favorite stories and poems, as well as key concepts he taught during his interprofessional course with students from the Schools of Nursing, Social Work and Medicine. His vision for the PCTC and this course is his enduring legacy.

Welcome to the Narrative Patient Centered Care online module. This module is presented in three parts:

I. Introduction to Narrative Patient Centered Care

II. Communication Skills for Narrative Patient Centered Care

III. Caring for the Whole Person and Family

In Part I, Introduction to Narrative Patient Centered Care, you will read essays and poems that explore loss and mortality and engage in self-reflection exercises that help you explore these deeply personal experiences.

UW photos, Northwest Scenes

As members of the health care team, we are often trained to identify and fix problems based on our professional experience.

Loss and mortality, however, are inevitable events to be lived, not problems to be solved.

Living with serious illness is an ongoing process occurring within a community.

The work of the healthcare team is to help each member of that community – patient, family and ourselves – live the best quality life possible as this process evolves.

Adapted from Farber,

Egnew & Farber 2004

A. Doorenbos, pain module

. . . I’ve endured a few knocks but missed worse. I know how lucky I am, and secretly tap wood, greet the day, and grab a sneaky pleasure from my survival at long odds. The pains and insults are bearable. My conversation may be full of holes and pauses, but I’ve learned to dispatch a private Apache scout ahead into the next sentence, the one coming up, to see if there are any vacant names or verbs in the landscape up there. If he sends back a warning, I’ll pause meaningfully, duh, until something else comes to mind.

On the other hand, I’ve not yet forgotten Keats or Dick Cheney or what’s waiting for me at the dry cleaner’s today. As of right now, I’m not Christopher Hitchens or Tony Judt or Nora Ephron; I’m not dead and not yet mindless in a reliable upstate facility. Decline and disaster impend, but my thoughts don’t linger there. It shouldn’t surprise me if at this time next week I’m surrounded by family, gathered on short notice—they’re sad and shocked but also a little pissed off to be here—to help decide, after what’s happened, what’s to be done with me now. It must be this hovering knowledge, that two-ton safe swaying on a frayed rope just over my head, that makes everyone so glad to see me again. “How great you’re looking! Wow, tell me your secret!” they kindly cry when they happen upon me crossing the street or exiting a dinghy or departing an X-ray room, while the little balloon over their heads reads, “Holy shit—he’s still vertical!” . . .

. . . A few notes about age is my aim here, but a little more about loss is inevitable. “Most of the people my age is dead. You could look it up” was the way Casey Stengel put it. He was seventy-five at the time, and contemporary social scientists might prefer Casey’s line delivered at eighty-five now, for accuracy, but the point remains. We geezers carry about a bulging directory of dead husbands or wives, children, parents, lovers, brothers and sisters, dentists and shrinks, office sidekicks, summer neighbors, classmates, and bosses, all once entirely familiar to us and seen as part of the safe landscape of the day. It’s no wonder we’re a bit bent. The surprise, for me, is that the accruing weight of these departures doesn’t bury us, and that even the pain of an almost unbearable loss gives way quite quickly to something more distant but still stubbornly gleaming. The dead have departed, but gestures and glances and tones of voice of theirs, even scraps of clothing—that pale-yellow Saks scarf—reappear unexpectedly, along with accompanying touches of sweetness or irritation.

The narrative approach draws upon the humanities, especially literary studies, biopsychosocial medicine and patient centered care to create a new framework for clinical care that is empathic, self-reflective, professional and trustworthy.

The goal is to "imbue the facts and objects of health and illness with their consequences and meaning for individual patients and [clinicians]."

Charon 2001

A. Doorenbos, pain module

Goals-of-care discussions, which are rooted in patient values, are associated with less aggressive care near the end of life and earlier hospice referral. Less aggressive care is associated with better quality of life and better adjustment for caregivers.

Zhang, Wright, Ray 2008.

The patient and family who are dealing with serious illness are almost always novices navigating a frightening road through the powerful culture of medicine.

You have a unique opportunity to help the patient and family create an individualized roadmap for a future that feels uncertain and walk alongside them in their journey.

When you know the patient’s story you can tailor your responses to meet the patient’s needs.

UW Medicine Photo Library ARNP Barbara Moravec

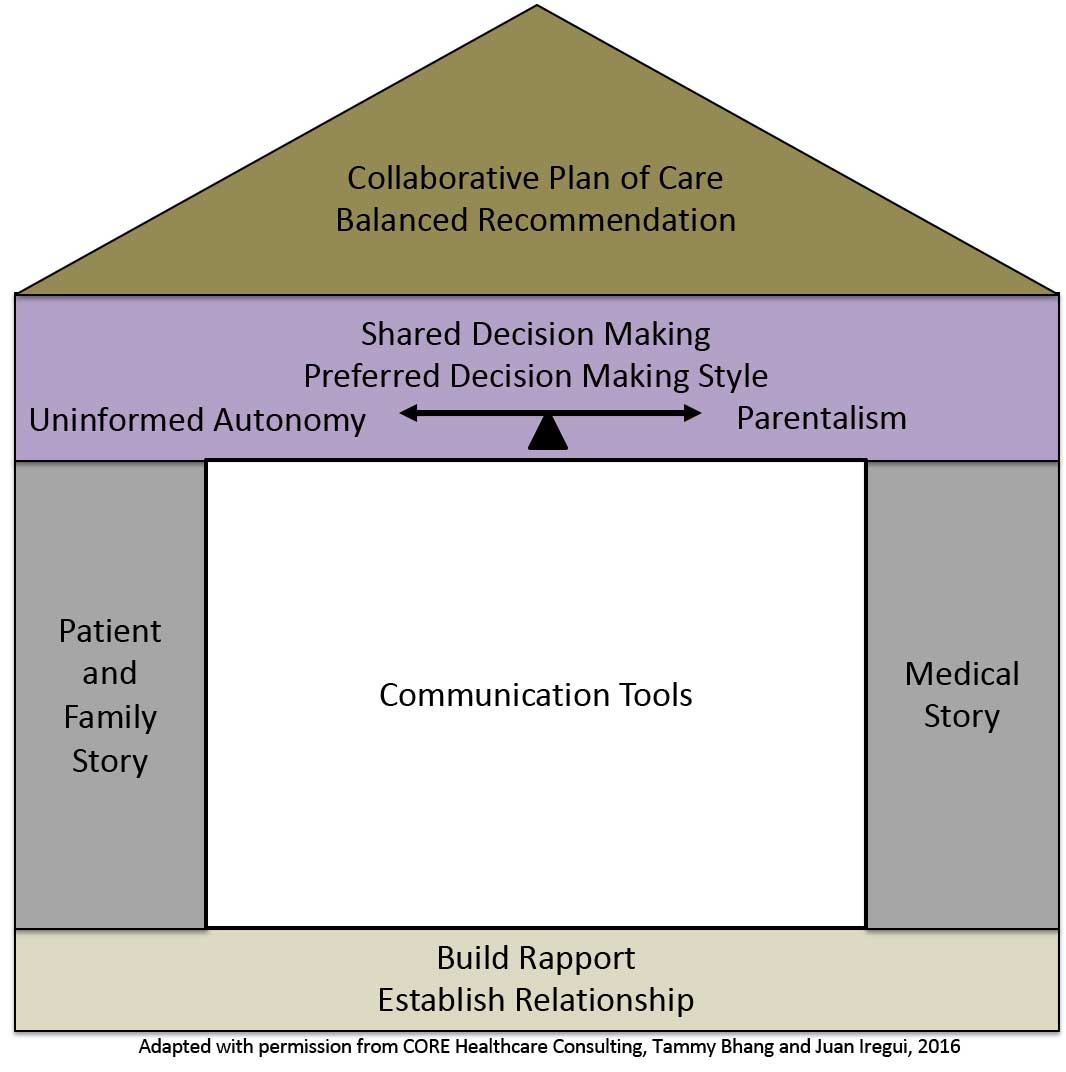

The house model offers a simple way to visualize the complexity of Narrative Patient Centered Care.

The house rests on a foundation which represents the trusting relationship the healthcare team establishes with the patient and the family. Without the foundation, there can be no house.

The wall to the left represents the patient and family story – their world beyond the illness, how the illness affects day to day life, their hopes and concerns for the future.

The wall to the right represents the medical story – the prognosis, treatment options, team member perspectives.

In the center of the house are the communication tools we use as clinicians to elicit the patient/family story and the medical story.

The roof of the house represents the integration of these narratives. This common narrative is the basis for shared decision making and enables clinicians to provide a balanced, values-based, recommendation.

The house model can be used to visualize Narrative Patient Centered Care conversations across the continuum of palliative care.

Adapted from Bhang, Iregui 2013.

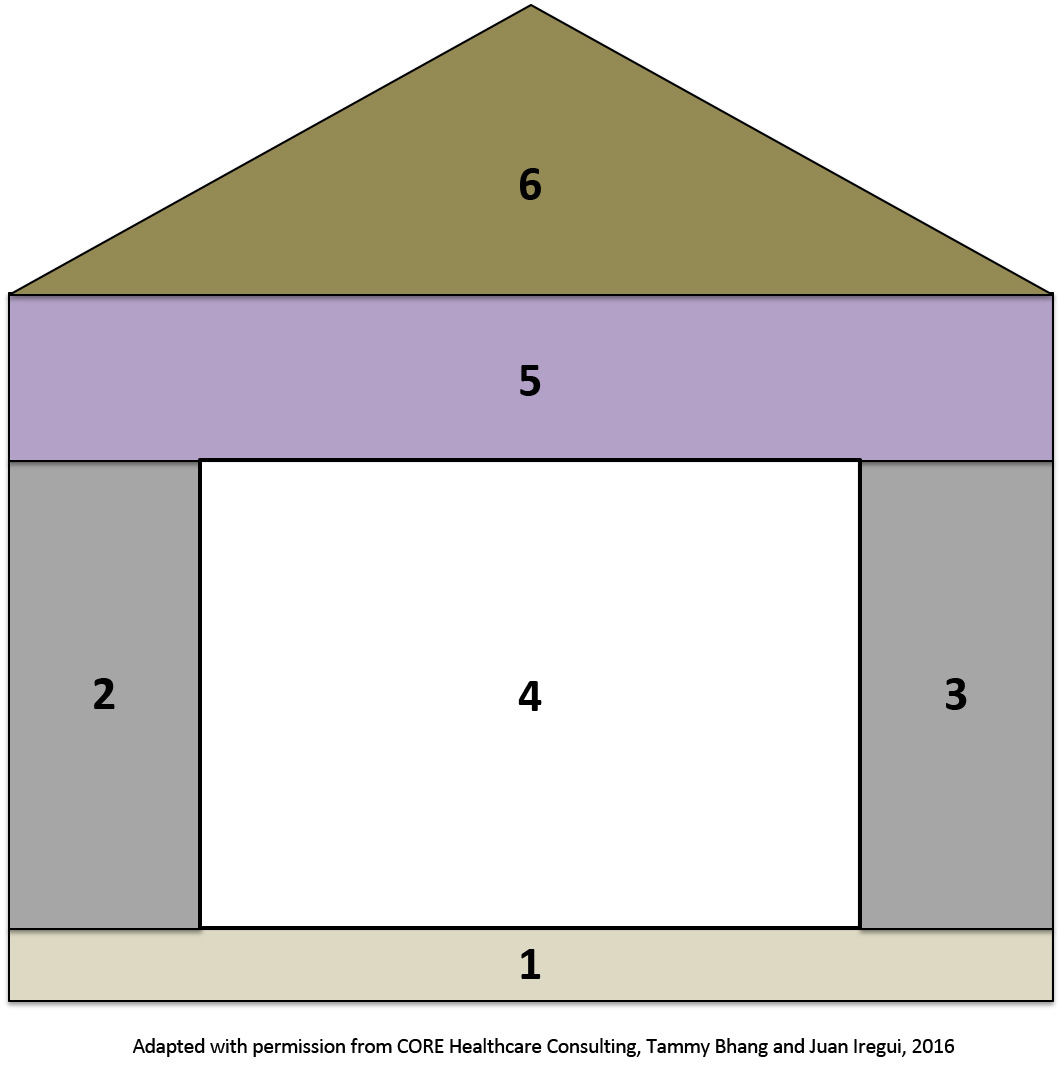

Imagine you are meeting a patient and their family for the first time.

Label the numbers to the right for each part of the House Model.

This will form the blueprint for the conversation you will have during your visit.

When you are done, click “feedback” to compare your answers.

1 Build Rapport and Establish Relationship

2 Patient and Family Story

3 Medical Story

4 Communication Tools

5 Shared Decision Making and Preferred Decision Making Style

6 Balanced Recommendations and a Collaborative Plan of Care

There’s a thread you follow. It goes among

things that change. But it doesn’t change.

People wonder about what you are pursuing.

You have to explain about the thread.

But it is hard for others to see.

While you hold it you can’t get lost.

Tragedies happen; people get hurt

or die; and you suffer and get old.

Nothing you do can stop time’s unfolding.

You don’t ever let go of the thread.

from The Way It Is: New and Selected Poems, 1998

Written 26 days before he died.

It takes self-awareness to recognize and name the “thread” we follow in our own lives.

Cultivating self-awareness is essential if we wish to avoid imposing our values and goals on patients and families – without even realizing we are doing so.

The key to Narrative Patient Centered Care is to be mindful of your own story and to practice self-reflection in real time during interactions with the patient and family.

A. Doorenbos, pain module

Pauline Chen, “First do no harm.” In Final Exam.

Pauline Chen

Think about a time when your story became entangled in the story of a patient you were caring for. What was this like for you?

Use the text box below to reflect on this experience.

Donald hall, the 83-year-old former poet laureate, was interviewed on NPR by Terry Gross on the subject of his 2012 New Yorker essay about what has been lost and what remains as he ages.

Hall says he no longer drives and laments his diminishing physical abilities, but still writes and remains cheerful.

"For 4 1/2 years now, I've hardly had a sad thought, except to curse a bit at my own clumsiness," he says. "... I am physically handicapped, but I can sit at my chair and work at my writing, and I want to do it every day. I enjoy it. I have to do draft after draft. ... It takes me a long time, but I love doing it, and I have to do it every day or I feel slack."

But Hall says he's now writing prose instead of poetry. That, too, is a function of growing older.

"I felt poetry slipping away," he says. "I'm not sure why. It was palpable. I've always felt that poetry was particularly erotic, more than prose was. ... I say that you read poems not with your eyes and not with your ears, but with your mouth. You taste it. This part of poetry, which is essential to me, seems to have diminished gradually until finally I really don't have it."

Hall says he also has trouble thinking of new subject matter.

"It used to be that phrases and lines would come into my head, often many of them in a period of five days or a week, and maybe I didn't know what I was talking about, but the words had a kind of heaviness or deliciousness to them," he says. "That's decreased. It's become less frequent until finally over the last few years, there's been none of that."

Click here to listen to Terry Gross’s interview with Donald Hall

UW photos, Cherry Blossoms

Read the full essay, “Out The Window: The view in winter,“ by Donald Hall in The New Yorker, January 23, 2012 at: Out The Window

Take a moment to think about the things that matter most to you. Think about tangible things – your relationships, pets, home, activities, skills, vacations, possessions – that you value and that give meaning to your life.

Using the space below, type 10 things you value most highly.

A. Doorenbos, pain module

Using the space below, reduce your list to 5 things you value most highly.

Using the space below, type a few sentences about your feelings as you considered losing 5 of your cherished values.

Using the space below, reduce your list to 3 things you value most highly.

Using the space below, type a few sentences about your feelings as you considered further reducing your list of cherished values.

Using the space below, type the 1 thing you value most highly, the 1 thing that makes your life worth living.

Using the space below, write a short paragraph about your feelings as you considered life with only this one cherished thing. Did this value surprise you? What is it about this value that makes it more important than those you gave up? Would you go back and exchange it for another? Add any other thoughts or insights.

Palliative care grew out of a movement to improve the dying experience of patients in the hospital setting. Over time, this movement has transformed to advocate for goal-concordant care across settings, care which aligns with an individual’s personal values, regardless of outcome or stage of illness.

The term “respectful death” emphasizes a nonjudgmental relationship among the members of a caregiving community – patient, family, and the healthcare team.

It acknowledges differences and allows for a shared process of integrating differences into as coherent a whole as possible. This shared point of view allows patients, families, and clinicians to embrace differences as valid and worthwhile.

The challenge comes in weaving these differing perspectives into a whole cloth that supports as many of the common values as possible for all parties.

Respect guides all participants to act within a community where the patient, family and clinicians act upon, as well as with, each other.

For respect to flourish, each member must be mindful of the others and strive to understand their values and goals.

A respectful death calls for a process of exploring the goals, values and meanings held by all involved, rather than prescribing the elements of a “good” death. For some dying at home is a priority and for others, dying in an ICU, fighting until the last minute is important. The role of palliative care clinicians is to elicit the story and how its meaning translates into “respectful care” along the illness trajectory, and eventually a “respectful death.” At times, this includes supporting patients and their families even when their core values differ from our own. This is at the heart of providing goal-concordant care.

Adapted from Farber, Egnew & Farber 2004

A. Doorenbos, pain module

If I'm lucky, I'll be wired every whichway

in a hospital bed. Tubes running into

my nose. But try not to be scared of me, friends!

I'm telling you right now that this is okay.

It's little enough to ask for at the end.

Someone, I hope, will have phoned everyone

to say, "Come quick, he's failing!"

And they will come. And there will be time for me

to bid goodbye to each of my loved ones.

If I'm lucky, they'll step forward

and I'll be able to see them one last time

and take that memory with me.

Sure, they might lay eyes on me and want to run away

and howl. But instead, since they love me,

they'll lift my hand and say "Courage"

or "It's going to be all right."

And they're right. It is all right.

It's just fine. If you only knew how happy you've made me!

I just hope my luck holds, and I can make

some sign of recognition.

Open and close my eyes as if to say,

"Yes, I hear you. I understand you."

I may even manage something like this:

"I love you too. Be happy."

I hope so! But I don't want to ask for too much.

If I'm unlucky, as I deserve, well, I'll just

drop over, like that, without any chance

for farewell, or to press anyone's hand.

Or say how much I cared for you and enjoyed

your company all these years. In any case,

try not to mourn for me too much. I want you to know

I was happy when I was here.

And remember I told you this a while ago - April 1984.

But be glad for me if I can die in the presence

of friends and family. If this happens, believe me,

I came out ahead. I didn't lose this one.

Where Water Comes Together with Other Water: Poems 1985

Raymond Carver, who died from lung cancer at the age of 50, had a clear idea about what dying well would look like for him. What does dying well mean to you? Are you able to imagine your own death? What do you want for your patients? Loved ones?

Use the text box below to reflect on what dying well means to you.

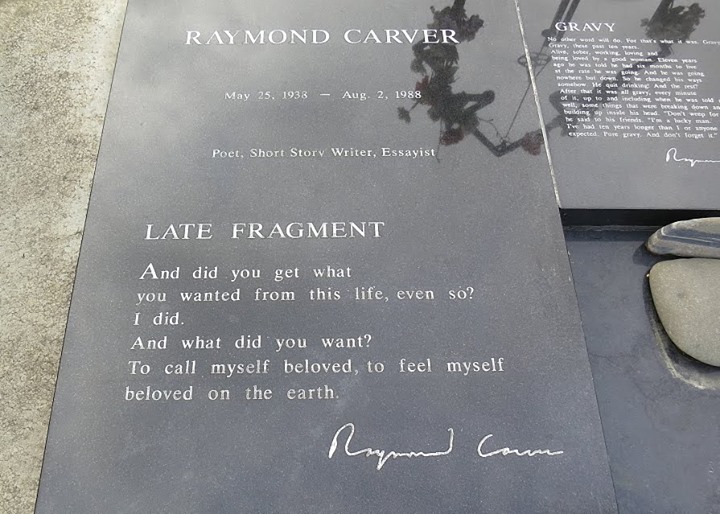

And did you get what

you wanted from this life, even so?

I did.

And what did you want?

To call myself beloved, to feel myself

beloved on the earth.

One of two poems inscribed on Raymond Carver’s tombstone and Stu Farber’s favorite poem.

UW photos, Northwest Scenes

Bhang TN, Iregui JC. Creating a climate for healing: a visual model for goals of care discussions. Journal of Palliative Medicine. 2013 Jul; 16(7):718.

Charon R. Narrative Medicine: A Model of Empathy, Reflection, Profession, and Trust. JAMA 2001; 286(15):1897-1902.

Chen P. “First, Do No Harm.” In: Final Exam. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2007

Farber, S., Egnew, T., Farber. “A. Respectful Death.” In: Living with Dying. J. Berzoff & P. R. Silverman, Eds. New York: Columbia University Press, 2004: 102-127.

Farber, L., Farber S. “A Respectful Death: The Power of Relationship in End-of-Life Care.” In: When Professionals Weep. R. S. Katz RS & T. A. Johnson TA, Eds., New York: Routledge, 2006: 221-236.

Gawande, A.,” Letting Go.” In: Being Mortal. New York: Metropolitan Books, 2014. An earlier version appeared at here

Wright, A. A., Zhang, B., Ray, A. Associations Between End-of-Life Discussions, Patient Mental Health, Medical Care Near Death, and Caregiver Bereavement Adjustment. JAMA. 2008;300(14):1665-1673