Setting goals and making a plan for achieving them fosters hope and allows individuals and families to feel they have some control in their lives. As healthy aging progresses or incurable illness advances, individuals will change and adapt their health care goals. Negotiating, reassessing and revising goals of care are continuing responsibilities for the health care team.

Setting goals of care can be especially challenging when the patient and the health care team do not share the same cultural assumptions about incurable illness and end-of-life care. In this unit, you will consider the role of culture in setting goals of care and learn communication techniques for eliciting the patient’s values and preferences.

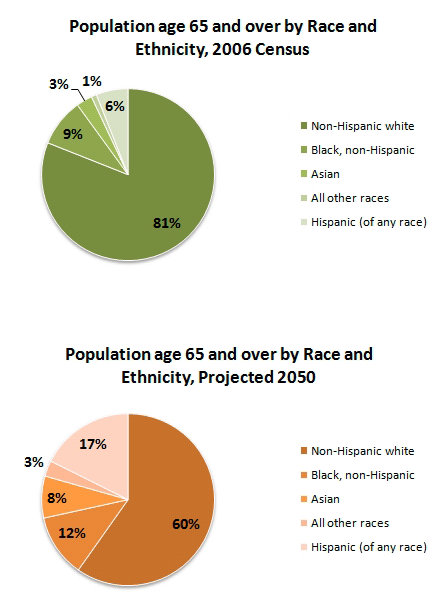

The US population is aging and growing more diverse.

There are many ways of thinking about culture. For some, culture is ethnic background, for others it’s customs and beliefs, and for still others, culture is seen as artifacts in a museum.

In the clinical setting, it is helpful to think of culture as the process of making meaning, building social relationships, and shaping the world that we inhabit.

Taylor 2003

Participants in a clinical encounter are engaging in the cultural process, whether as patients monitoring their health and seeking remedies or as practitioners diagnosing and treating disease.

Patients and families bring culturally shaped understandings of their illness and its meaning in their lives to the clinical encounter.

Heath care practitioners carry understandings of disease and the patient’s best interest that are shaped by their culture of origin and the culture of Western medicine.

These understandings are shared and modified in the clinical exchange of information between patients and the health care team.

Kleinman, Eisenberg, & Good 1978

Learning culture-specific rules for caring for diverse patients is neither effective nor realistic and can lead to stereotyping.

It is useful, however, to be aware of core values that may lead to cultural conflicts. These include preferences for gender roles, physician authority, physical space, family roles, and communication, as well as beliefs and practices about disease, spirituality, and death.

Searight & Gafford 2005

The following examples are well documented. Perhaps you have observed similar values that conflicted with biomedical ethical values in your practice:

Differences in underlying cultural assumptions about health, illness, dying, and treatment may mean that the health care team must modify their approach to setting goals for care.

It may be useful for this conversation to take place in the context of a family meeting so that all can hear the same information.

The vulnerability of the patient and the authority of the physician often lead to an uneven exchange in which the practitioner’s understandings are imposed on the patient without equal attention to the patient’s values and beliefs.

The unequal exchange between patient and physician occurs even when both share the same culture and is further complicated when their underlying values and experiences are shaped by different cultures.

Jecker et al. 1995

EPEC-O. Education in Palliative and End-of-life Care - Oncology

Pa Lee, 61, is in hepatic failure and has chronic hepatitis B. She was admitted to the intensive care unit through the Emergency Department with massive hematemesis due to bleeding from esophageal varices. The bleeding was stopped by endoscopic sclerosis of the varices. She is currently stabilized and on a medical floor.

Over the past six years, Mrs. Lee has been using a combination of herbal remedies (khawv koob), shamanistic ceremonies, and visits to the Emergency Department for her hepatitis and resultant failing liver. She does not have a primary care physician, but she has sought treatment at the local hospital Emergency Department several times for crises such as variceal bleeding.

Mrs. Lee has moderate ascites and has had one episode of spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP), which was resolved with intravenous (IV) antibiotics. She has had prior episodes of encephalopathy, a complication of her hepatitis, which were controlled with medication. She has difficulty eating because of her liver disease, and she has lost significant body mass.

Following an earlier variceal bleed, a beta-blocker and placement of a transcutaneous intrahepatic portal shunt (TIPS) were recommended, but the patient and family refused. Because of her advanced liver disease, Mrs. Lee is considered a high-priority candidate for a liver transplant, but she has refused this option in the past.

Adapted from Culhane-Pera, et al. 2003

To learn more about Hmong culture and health see Culhane-Pera, K. A., et al. (Eds.) Healing by Heart, Clinical and Ethical Case Stories of Hmong Families and Western Providers.

The hospital's treatment team expects that as Mrs. Lee's liver failure progresses, complications are inevitable, including further bleeding, progressive encephalopathy, and recurrent episodes of SBP. Dr. Thompson plans to discuss treatment options with Mrs. Lee, including reconsideration of the TIPS procedure, placement of a tube for artificial nutrition, and follow-up care after discharge.

Dr. Thompson visits Mrs. Lee and explains the options the treatment team would typically recommend for someone in her situation. She listens but resists making treatment decisions, explaining that she needs to consult with her husband, their uncle, Mr. Chang, and their shaman.

If you were Mrs. Lee's nurse practitioner, what would you do at this point?

Type a brief answer in the text box then click to see what Mrs. Lee’s physician decides to do.

Mrs. Lee is originally from the highlands of Laos, where her family were farmers. She has a large and supportive family in the U.S.

Mrs. Lee makes decisions about her health care after seeking the advice of the family and clan, particularly her husband and an older uncle, and is thus assured of their support when it is needed.

Culhane-Pera, et al. 2003

“The Hmong have a phrase, hais cuaj txub kaum txub, which means “to speak of all kinds of things.” It is often used at the beginning of an oral narrative as a way of reminding the listeners that the world is full of things that may not seem to be connected but actually are; that no event occurs in isolation; that you can miss a lot by sticking to the point; and that the storyteller is likely to be rather long-winded.”

Anne Fadiman, The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down: A Hmong Child, Her American Doctors, and the Collision of Two Cultures.

Explanatory Models answer questions about the identity, cause, duration, effects, and mechanisms of the illness, and address the patient's fears, problems, and expectations of treatment. The original questions have been adapted and used successfully by clinicians for years. You can adapt them so they are effective for you and your patients.

Dr. Thompson returns later that afternoon to check on Mrs. Lee. He is wondering why she would hesitate to have the TIPS procedure. He asks Mrs. Lee if they can discuss her illness.

Watch as Dr. Thompson begins by stating his wish to understand the patient’s decision.

How does your Explanatory Model of Mrs. Lee disease differ from hers? What implications does this difference have for what you would do next?

Type a brief answer in the text box. In a few minutes you will see what Mrs. Lee’s physician decides to do.

Perhaps you felt that you needed to learn more about Mrs. Lee’s beliefs. You may also have noted that you had an obligation to be sure she was making a fully informed decision. At the same time, you may have begun looking for common ground and a way to honor Mrs. Lee’s wishes.

L.E.A.R.N. is a mnemonic device that will help you organize your approach to eliciting information about the patient's culture and incorporating her preferences in the plan of care. The steps are:

The mnemonic is not meant to be restrictive, but rather to guide you in allowing patients to take center stage as the experts on their illness and culture.

The next morning, Dr. Thompson returns to talk with Mrs. Lee about the decisions she made with her husband and uncle.

Watch their conversation and rate how effectively the physician used L.E.A.R.N. in the interaction.

The exchange between Dr. Thompson and Mrs. Lee reveals that Explanatory Models, like the culture they embody, are dynamic and change in response to events in their environment.

Dr. Thompson and Mrs. Lee completed all five steps of L.E.A.R.N. in order to arrive at a plan of care for Mrs. Lee that respected her beliefs and values and allowed her to make informed choices.

It will not always be possible or appropriate to complete L.E.A.R.N. in one conversation. You may need to complete the steps over several discussions and adapt the order and focus according to your patient's needs.

Cultural values and preferences around goals of care may vary as much among members of the same culture as they do between members of different cultures.

Intra cultural diversity is shaped by gender, age, class, education, acculturation, and life opportunities and may mean that even members of the same family do not fully share the same culture.

Intra cultural diversity may account for differences in health-seeking behaviors and decision making among members of the same cultural groups.

Hern et al., 1998

Stereotyping is best avoided by asking the patient about her values, beliefs, and preferences.

Culture is a process by which all people make sense of their lives, order their relationships, and shape their world.

Explanatory Models and LEARN provide frameworks for inquiring about and understanding culture processes.

Berlin, E. A., Fowkes, W. “A Teaching Framework for Cross-cultural Health Care.” Western Journal of Medicine 1983; 139:934-938.

Culhane-Pera, K. A., Wawter, D. E., Phua Xiong, Babbitt, B., & Solberg, M. M. (Eds.) Healing by Heart, Clinical and Ethical Case Stories of Hmong Families and Western Providers. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press, 2003.

Culhane-Pera, K. A., Vawter, D. E. “A study of healthcare professionals' perspectives about a cross-cultural ethical conflict involving a Hmong patient and her family.” Journal of Clinical Ethics 1998; 9(2), 179-190.

EPEC-O. Education in Palliative and End-of-life Care - Oncology. Module 9 – Negotiating Goals of Care. National Cancer Institute.

Fadiman, A. The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down: A Hmong Child, American Doctors, and the Collision of Two cultures. New York: Farrar, Strauss, and Giroux, 1997.

Hern, H. E., Jr., Koenig, B. A., Moore, L. J., & Marshall, P. A. “The difference that culture can make in end-of-life decision making.” Cambridge Quarterly of Health Ethics 1998; 7(1), 27-40.

Jecker, N. S., Carrese, J. A., Pearlman, R. A. “Caring for patients in cross-cultural settings. Hastings Center Report 1995; 25(1), 6-14.

Kleinman, A., Eisenberg, L.” Culture, illness, and care: Clinical lessons from anthropologic and cross-cultural research.” Annals of Internal Medicine 1978; 88(2), 251-258.

Kleinman, A. Patients and healers in the context of culture: an exploration of the borderland between anthropology, medicine and psychiatry. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980.

Searight, R.H. & Gafford, J. “Cultural Diversity at the End of Life: Issues and Guidelines for Family Physicians.” American Family Physician 2005; 71(3): 515-522.

Stone, M.J. “Goals of Care at End of Life.” Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings 2001; 14(2): 134 – 137.

Taylor, J. S. “The story catches you and you fall down: tragedy, ethnography, and “cultural competence.” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 2003; 17(2): 159-181.

True, G., & Allman, R. “Hmong patient's end-of-life goals foreign to western physician.” In E. Phipps & P. Pennese (Eds.). Last Acts statement on diversity and end-of-life care. Washington, D.C.: Last Acts National Program Office, 2001: 5 – 7.

This work was supported in part by grants from the Cambia Health Foundation and the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Cambia Health Foundation or the National Institute of Nursing Research.

Understanding your patient’s story, including their illness and life beyond their illness, helps you provide them the best care possible. These modules, presented in three parts, will introduce you to the communication skills needed to elicit the patient and family narrative.

This module briefly reviews the Triple Aim for improving health care, presents a video case study in which the Triple Aim is not met, and analyzes types of interprofessional conflict and strategies for resolving them.

After completing this module you will be able to:

Setting goals and making a plan for achieving them fosters hope and allows individuals and families to feel they have some control in their lives. As healthy aging progresses or incurable illness advances, individuals will change and adapt their health care goals...

The number of individuals who speak English with limited proficiency (LEP) or who don't speak the language at all is growing in the United States as the population becomes more diverse. Language differenced can create barriers between practitioners and patients and affect the quality of patient care.

In the case of Mrs. Rodriguez, you will learn how professional interpreters facilitate important clinical communication, enhancing the patient-practitioner relationship and the quality of care....

Given how much there is to learn about facilitating family conferences, focusing attention on emotions may seem like a strange use of time. However, we’ve found that effectively addressing patient and family emotions helps avoid many of the common pitfalls in these encounters, including conflict...

Patients, families and members of the interprofessional palliative care team draw upon deeply held personal values and professional standards to set goals of care.

Differing values and standards for care may give rise to conflicts between...

Patients with chronic or life-limiting disease may supplement their treatment with complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). However, less than 40% of patients tell their provider about their CAM use. Even when the physician asks them directly, they may be reluctant to discuss their CAM use....

Stone, M.J. 2001, “Goals of Care at End of Life.” Baylor University Medical Center Proceedings 2001; 14(2): 134 – 137.

EPEC-O. Education in Palliative and End-of-life Care - Oncology. Module 9 – Negotiating Goals of Care. National Cancer Institute