Patients and families who have experienced discrimination historically and in the present may distrust the health care system.

In this module, you will meet the Johnsons, an African American family, who appear to distrust the hospice team’s suggestion that it's time to discontinue tube feeding for their loved one.

Mr. Johnson is a 79-year-old African-American male who presented to the Emergency Department in the late evening with difficulty speaking and right-sided weakness. In the ED, Mr. Johnson was diagnosed with Transient Ischemic Attack (TIA). He was admitted to the ICU. The next day, Mr. Johnson suffered a massive Cerebral Vascular Attack (CVA). He remained in the ICU and showed no improvement.

Mr. Johnson has been receiving medical care in the Hypertension Clinic for many years. During his last visit, his physician informed him that his hypertension was worsening. They set a goal for Mr. Johnson to lose 20 pounds and walk 15 minutes each day to increase his activity level.

In light of Mr. Johnson's worsening hypertension, the physician raised the subject of Advance Care planning. Mr. Johnson informed his physician that he would "not want to be kept alive if my mind is gone." They agreed that Mrs. Johnson should be present to continue this discussion at the next visit.

The Johnson family shares a mix of experiences with the health care system. Mr. Johnson has learned to count on his pulmonologist and to talk frankly with him, but for most of his adult life he avoided physicians. He still speaks of his brother who was so fearful of mistreatment that he refused to seek care for a strangulated hernia and died.

Mrs. Johnson encourages her husband to keep his appointments and take his medications as ordered. She is, however, skeptical of the care that black people receive. Like many of her friends and family, she believes that African American men were inoculated with syphilis for the Tuskegee experiment and observed as they slowly died without treatment.

Despite aggressive medical treatment, including thrombolytic therapy, Mr. Johnson remained unresponsive to his environment. A consultation with the neurologist confirmed that Mr. Johnson had suffered major brain injury from the stroke and was unlikely to regain consciousness or function.

His physician from the Hypertension Clinic stopped to see Mr. Johnson and was surprised to see that a feeding tube had been placed at the family's request. He made a note in the patient's chart that Mr. Johnson would have been likely to refuse a feeding tube in his current condition.

Three days later, Mr. Johnson was transferred to a skilled nursing facility for care. The family had not agreed to hospice care, but agreed to meet with the hospice team at the facility.

The hospice social worker arranges a meeting with Mrs. Johnson and her adult son and daughter. They review the hospice referral information together. The family is understandably upset about the prospect that Mr. Johnson will not awaken or return to his old self.

During the discussion, the social worker points out that the referral note mentioned Mr. Johnson's preference for refusing a feeding tube if he could not recover to his previous level of functioning.

The son acknowledges that he has heard his father make such statements, but the wife and daughter are adamant that Mr. Johnson be maintained on the feeding tube. They refuse to continue discussion about the feeding tube. They reluctantly agree to admit him to hospice, but state that they continue to hope that he will wake up.

Type your answer in the text box below.

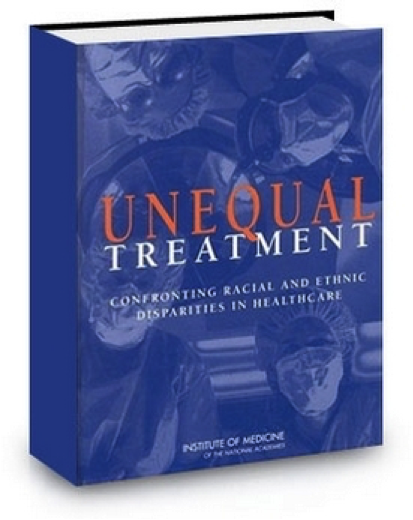

Life expectancy of African Americans is seven years less than whites. African Americans have higher rates of cardiovascular disease, many types of cancer, diabetes, infant mortality, hypertension, homicide, and unintentional injuries than whites.

For all diseases, African Americans receive treatment later in the disease process when the condition is more advanced.

Smedley, Stith, & Nelson, 2003

You realize that people who have experienced discrimination, historically or currently, may mistrust the health care system. But what can you do about it when providing care to African American patients like Mr. Johnson?

Type your answer in the text box below.

Crawley, 2002 and 2004

Over the next week, there are no signs of improvement in Mr. Johnson's condition.

At least one member of Mr. Johnson's family is sitting at his bedside whenever the social worker visits. On each of these occasions, she asks them whether they have any questions and whether Mr. Johnson appears comfortable to them. They tell her that he appears to be resting, but volunteer little conversation.

The hospice social worker realizes that Mrs. Johnson and her daughter may not trust her or the health care system, and that they may not feel safe expressing their misgivings to her. She decides to start the conversation with Mrs. Johnson.

Listen as she begins the conversation.

By showing interest in Mrs. Johnson' concerns, the social worker made it safer for her to talk about her family's experiences.

Mr. Johnson has shown no signs of improvement. The social worker discusses options for this care with Mrs. Johnson.

Ask clients and their families about their values.

Identify your own values and recognize how they may influence communication and expectations

Work from the place of shared values.

The social work continues the conversation with Mrs. Johnson and her son joins them.

Work from the place of shared values.

After the feeding tube was stopped, the minister and several choir members from Mr. Johnson's church prayed and sang for him at his bedside. Mr. Johnson died quietly a few days later with his family at his side.

His daughter joined her mother and brother for her father's final hours, but did not support the plan to discontinue the feeding tube and refused to speak further about it.

Patients and families who have experienced discrimination, historically and in the present, may distrust the health care system. Because they may not feel safe expressing their mistrust, you may need to ask about their experiences and fears.

It's up to you to demonstrate your trustworthiness. Asking about, listening to, and acknowledging the patient's and family's concerns are key to establishing trust.

When the family feels that their concerns are heard, points of agreement can be found for establishing a plan of care.

Even so, you may not succeed in gaining the trust of all family members.

Crawley, L. Living in the face of death: the African-American experience. Last Acts Partnership Call, Issues barriers and opportunities to palliative care. 2004, April 2.

Crawley, L., Marshall, P., Lo, B., Koenig, B. Strategies for culturally effective end-of-life care. Annals of Internal Medicine, 2002; 136, 673-679.

Rhodes, R.L, Xuan, L., Halm, E. A. African American Bereaved Family Members' Perceptions of Hospice Quality: Do Hospices with High Proportions of African Americans Do Better? Journal of Palliative Medicine, 2012 Oct; 15(10): 1137–1141.

Smedley, B. D., Stith, A. Y., & Nelson, A.R. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press. 2003

This work was supported in part by grants from the Cambia Health Foundation and the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Cambia Health Foundation or the National Institute of Nursing Research.

This module is presented in three online units:

This module briefly reviews the Triple Aim for improving health care, presents a video case study in which the Triple Aim is not met, and analyzes types of interprofessional conflict and strategies for resolving them.

After completing this module you will be able to:

Setting goals and making a plan for achieving them fosters hope and allows individuals and families to feel they have some control in their lives. As healthy aging progresses or incurable illness advances, individuals will change and adapt their health care goals...

The number of individuals who speak English with limited proficiency (LEP) or who don't speak the language at all is growing in the United States as the population becomes more diverse. Language differenced can create barriers between practitioners and patients and affect the quality of patient care.

In the case of Mrs. Rodriguez, you will learn how professional interpreters facilitate important clinical communication, enhancing the patient-practitioner relationship and the quality of care....

Given how much there is to learn about facilitating family conferences, focusing attention on emotions may seem like a strange use of time. However, we’ve found that effectively addressing patient and family emotions helps avoid many of the common pitfalls in these encounters, including conflict...

Patients, families and members of the interprofessional palliative care team draw upon deeply held personal values and professional standards to set goals of care.

Differing values and standards for care may give rise to conflicts between...

Patients with chronic or life-limiting disease may supplement their treatment with complementary and alternative medicine (CAM). However, less than 40% of patients tell their provider about their CAM use. Even when the physician asks them directly, they may be reluctant to discuss their CAM use....