In the second unit, Communication Skills for Narrative Patient-Centered Care, you will complete an interactive video case study in which you observe, critique and reflect on the skills needed for a narrative approach to Patient-Centered care.

"Never forget that you are also a story teller, that we live in stories the way fish swim in water, that we choose our stories, that we are made of stories."

Rebecca Solnit, author

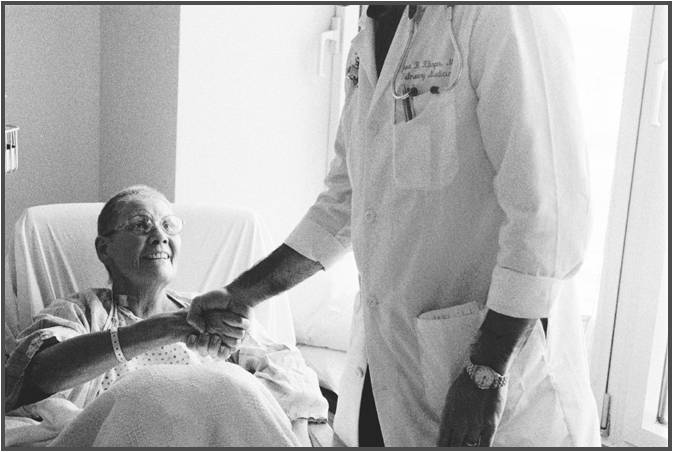

He said it doesn't look good

he said it looks bad in fact real bad

he said I counted thirty-two of them on one lung before

I quit counting them

I said I'm glad I wouldn't want to know

about any more being there than that

he said are you a religious man do you kneel down

in forest groves and let yourself ask for help

when you come to a waterfall

mist blowing against your face and arms

do you stop and ask for understanding at those moments

I said not yet but I intend to start today

he said I'm real sorry he said

I wish I had some other kind of news to give you

I said Amen and he said something else

I didn't catch and not knowing what else to do

and not wanting him to have to repeat it

and me to have to fully digest it

I just looked at him

for a minute and he looked back it was then

I jumped up and shook hands with this man who'd just given me

something no one else on earth had ever given me

I may have even thanked him habit being so strong.

From All of Us: Collected Poems by Raymond Carver

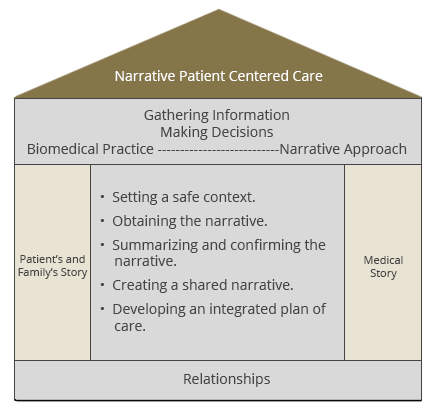

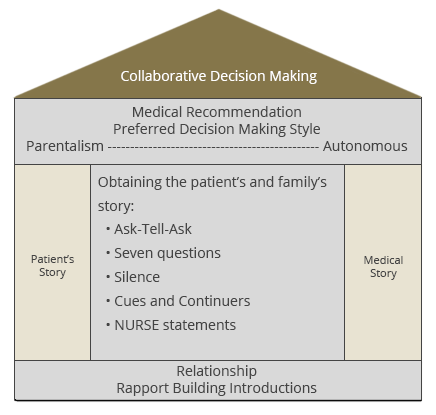

The skills needed for Narrative Patient-Centered Care will be described below and demonstrated in the video case study.

Bhang & Iregui 2013. Adapted with permission.

Underlying the skills needed for Narrative Patient-Centered Care is a significant difference in the approach you will take to gathering information and making decisions with patients and families.

Shifting from the familiar biomedical approach to the narrative approach is not easy. Biomedical culture has powerful effects on our interactions with patients and families that are often outside of our awareness (Chen, 2007 and Gawande, 2014).

Consider the challenge and the rewards as presented in this brief comparison.

Wendy Jones has been referred to your team for primary care because her previous primary care physician is no longer a provider in her Medicare insurance plan.

Wendy is a 67 year old woman with a history of good health until March of 2010.

A routine GYN exam revealed cervical cancer. A radical hysterectomy was done with clear margins and negative lymph node sampling. She recovered uneventfully but in February 2011 she was found to have recurrence in the pelvis on surveillance CT exam.

A second surgery was done for de-bulking and tissue confirmation followed by pelvic radiation and chemotherapy. She tolerated this treatment well and was again symptom free until six months ago when she developed a palpable recurrence on clinical exam.

The tumor failed to respond to several combinations of chemotherapy and the chemotherapy made her quite ill. Three weeks ago her symptoms of increasing large bowel obstruction from tumor necessitated a diverting colostomy.

She recovered well from surgery except for a small fistula. She continues to complain of significant pain despite large doses of Percocet.

Most patients and families are accustomed to medical discussions focused on their disease with clinicians doing most of the talking.

For the patient and family, being asked to share their story in a healthcare setting is likely to be a new experience. It’s a discussion they are probably not expecting or prepared to have.

Watch the videos to observe Wendy’s first encounter with her new primary care physician. In the first video, the physician follows standard biomedical practices, in the second he takes a narrative Patient-Centered approach. After watching each video you will be asked to identify the communication skills you observed.

Obtaining the patient's and family's "story" requires a considerable shift from the traditional medical interview. The communication skills presented in this unit will help you facilitate narrative based discussions. We will revisit these skills during Wendy’s follow-up visit in the final unit as well.

Bhang & Iregui 2013. Adapted with permission.

Patients often need much more than a few seconds to adequately self-reflect when answering questions such as “What are you hoping for?” or “What are you afraid of?”

Periods of silence lasting 7 to 15 seconds can be powerful invitations for a patient to share deeper values and meaning.

Silence is not the absence of communication but a rich opportunity for patients to access memories and experiences and provide deeper answers to our questions.

Research shows that the average physician can tolerate silence in a conversation for an average of 7 seconds.

“Patient cues” are verbal and non-verbal indications that the patient or a family member has unspoken emotionally charged concerns.

"Continuers" are verbal and non-verbal responses by the clinician that acknowledge the emotions being expressed and encourage the patient or family to share more about their concerns.

"Terminators" are verbal and non-verbal responses by the clinician that focus on biomedical facts and ignore the emotions patients and family are expressing.

Patients’ cues are windows of opportunity for exploring the patient's story in more depth and sharing deeper emotional, existential and spiritual truths that underscore values and meanings.

“Continuers” won’t work with everyone. Not all patients are comfortable with sharing their emotions.

If you use “continuers” and get little response, be respectful of the patient’s and family’s limits and stay within the boundaries they set in sharing their story.

Observe the differences in the attempts to obtain Wendy’s story in the videos below. After watching each video you will be asked to identify the communication skills you observed.

"NURSE" is an acronym for statements that acknowledge the patient's and family’s emotional concerns and create an opportunity for them to tell you how they feel.

"NURSE" statements are “continuers” that help you open the windows of opportunity provided by patient "cues."

After obtaining the patient’s and family’s story, summarize and confirm what you’ve heard.

Summarizing and confirming the narrative creates a path to common understanding.

Observe the differences in the attempts to summarize and confirm Wendy’s story in the videos below. After watching each video, you will be asked to rate the physician’s use of Narrative Patient-Centered communication skills.

Assist everyone – patient, family and primary care team – in integrating shared and differing values and goals into a common understanding of how to live the best life possible within the context of available medical and social resources.

For example, patients and families often differ significantly from the healthcare team in their understanding of the benefits of code status and resuscitation.

Helping the patient and family understand how resuscitation helps them meet their quality-of-life goals or increases their pain and suffering is more effective than sharing statistics on survival.

Patients rarely choose medical treatments as ends in themselves. They choose them as a way to live a meaningful life.

Observe the differences in the attempts to create a shared narrative and plan of care for Wendy in the videos below. After watching each video, you will be asked to identify the communication skills you observed.

In the third unit, you will observe Wendy’s follow-up visit with her physician and learn about Whole Person dimensions of Narrative Patient-Centered Care.